Reclaiming Language: A Conversation With Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

Shortly before his death, The Nation spoke with the Kenyan writer about his most recent essay collection Decolonizing Language and Other Revolutionary Ideas.

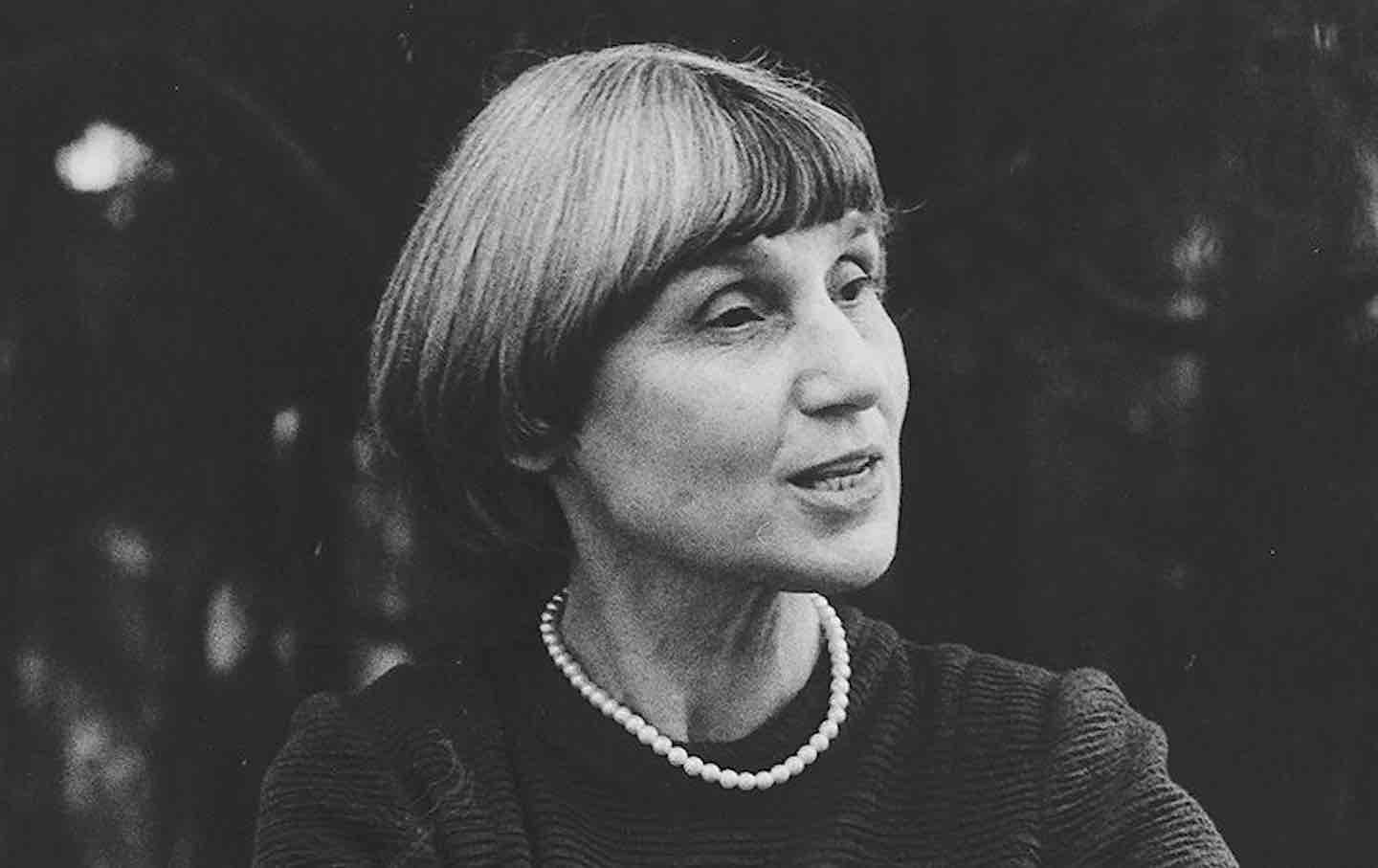

The novelist, playwright, and essayist Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s life and work have come to symbolize some of the most urgent questions facing postcolonial Africa—about language, memory, justice, and the enduring legacies of empire. A perennial favorite to receive the Nobel Prize for literature, the Kenyan writer died on May 28 in Atlanta at the age of 87; his death was announced by his daughter Wanjikū Wa Ngũgĩ.

Born in 1938 in Kamirithu, a village north of Nairobi, Ngũgĩ came of age under British colonial rule during the height of the Mau Mau rebellion. One brother joined the resistance, another was killed, and his mother was arrested and tortured. At Alliance High School, a mission-run institution where speaking his native Gĩkũyũ could get a student beaten, Ngũgĩ was inducted into what he would later call “colonies of the mind”—a system where English was not only the language of instruction, but of power.

Ngũgĩ studied English at Makerere University in Uganda and at Leeds University in England, where he began writing fiction that probed the psychological aftermath of colonialism. His early novels—Weep Not, Child (1964), The River Between (1965), and A Grain of Wheat (1967)—composed in English and written under the name James Ngugi, established him as a major voice in the growing canon of mid-20th-century African literature, alongside figures such as Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka. But the critical success of these works left him uneasy. “I knew about whom I was writing,” he later reflected in Moving the Centre (1993), “but for whom was I writing?” That question marked the beginning of a dramatic turn.

In the 1970s, Ngũgĩ helped found a community theater in Kamirithu and staged Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), a radical play written in Gĩkũyũ with Ngũgĩ wa Mĩriĩ and performed by workers and villagers. The play, which critiqued postcolonial elites, was banned by the government in 1977; the theater was razed by local authorities; and Ngũgĩ was imprisoned without trial. In his prison cell, he began writing Caitaani Mũtharabainĩ (Devil on the Cross), his first novel in Gĩkũyũ, on scraps of toilet paper. The defiant act marked a permanent break with English as his literary language.

In 1986, he published a work of memoir and theory called Decolonising the Mind, in which he made the case that language was a key site of colonial control and that reclaiming African languages was essential not only for cultural self-expression but for resisting the psychological legacy of imperial rule. As he wrote in one of the book’s oft-cited passages, “The cannon forces the body and the school fascinates the soul.”

His most recent collection of essays, Decolonizing Language and Other Revolutionary Ideas, develops this line of argument with fresh urgency. The book is divided into two parts: The first is focused on the production of knowledge in universities, the impact of globalization on African scholarship, and the government’s role in nurturing an ecosystem of African languages (he calls for the establishment of a Central Bureau of African Languages in every African country); the second part comprises tributes to, and reminiscences about several African writers and thinkers such as Soyinka, Achebe, and Grace Ogot. The book is animated by an insistence that language is not merely a vehicle for communication but a repository of knowledge and identity—and that true liberation begins when we reclaim the right to think, dream, and imagine in our own tongues. The Nation spoke with Ngũgĩ over e-mail last month about “linguistic feudalism,” Trump’s recent executive order designating English as the official language of the United States, and more. This interview has been edited for length and concision.

—Rhoda Feng

Rhoda Feng: One powerful thread across Decolonizing Language, Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature, and Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms is the call for African writers and intellectuals to produce work in the languages of the people. Do these works form a trilogy in your mind?

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o: They were not written as a trilogy, but I suppose one can call them a trilogy in a broad sense of the word. For instance, the language question figures prominently in all the three books. But underlying the language question is the question of knowledge. Knowledge is always from here to there in a dialectical progression of mutual illumination. This is in contrast with colonial education which assumes that all knowledge is a mono progression from the imperial center to all other places. Language is the starting point of all knowledge.

RF: Your critique of “linguistic feudalism” is one of this book’s most powerful interventions. How do you envision a more egalitarian model of linguistic exchange—one based not on dominance but on mutual enrichment?

NwT: All languages are repositories of knowledge. For instance, all languages have the best knowledge of the environment they come from. But languages can also give to each other. Translation is the best way of ensuring that all languages can talk to each other. In one of my other books, The Language of Languages, I have described translation as the common language of languages. It enables dialogue and sharing among all the languages of the earth.

RF: In Moving the Centre, you noted that African languages have been kept alive “in their most magical form” through orature, or oral literature. How do you think about form—as in, the form of the play, the proverb, the essay—as a site of resistance? Is there a form you still long to experiment with?

NwT: I would love to sing, but alas I don’t have the voice. The singers of all cultures help keep languages alive. Singing is part of orature. You don’t have to have a written script to sing a song.

RF: In an interview with LARB, you noted that “theater has had more impact on my life, including on the craft of fiction, than the novel. After all, it was a play that sent me to Kamĩtĩ Prison, where I rethought the whole language question and embarked on my first novel in Gĩkũyũ.” There’s a chapter in your new book dedicated to the work of Wole Soyinka, whom you call the “conscience of Africa.” Were there other playwrights who had a formative influence upon you as a writer?

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →William Shakespeare and Bertolt Brecht, come to mind. But there are also Irish like J.M. Synge. Russian playwrights of the 19th century, for instance Chekhov, also come to mind. I must confess that I have not kept up with all the contemporary playwrights.

RF: Are there other writers whom you consider “voices of prophecy” but were left out of your collection?

NwT: I think that all writers are voices of prophecy. Think of the biblical prophets. They were good with words. They spoke out their visions. But in the age of writing, they would have written down their visions.

RF: In her 2015 book The Fall of Language in the Age of English, the Japanese writer Minae Mizumura expressed concern that non-English literary traditions and languages—like that of modern Japanese—are being gradually hollowed out by English’s global dominance. Your own work argues that African languages were not just displaced but criminalized and buried under colonial education systems. I wonder if you see any affinities between your work and the work of Mizumura.

NwT: I think it was Winston Churchill who said that the empires of the future will be empires of language. The dominance of English is a reflection of the global reach of British and American imperialism, both English-speaking empires.

RF: What do you make of the recent moves to “decolonize” syllabi in Western universities? Can this work be meaningful if not conducted in African languages themselves?

NwT: This is good. Colonialism involves both the colonizer and the colonized. Real decolonization must involve both parties. In Africa, the language question is central to decolonization. Linguistic hierarchy affects the whole world.

RF: So much of your work champions the vitality or living presence of Gĩkũyũ. How do you resist the museumification of African languages, especially as your own works enter university syllabi worldwide?

I advocate the equality of all languages, big and small. Languages are like all living organisms. They have to grow, but growth involves shedding off of dead skins and then comes the flower, which contains the future of that plant.

RF: In a 2018 essay for LitHub, your son Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ noted that “today, more and more younger African writers are taking up Ngugi’s call while taking advantage of the Internet age.… Whereas my generation inherited the language anxieties of the Makerere generation, the work of the Jalada Collective points to a generation that is more confident, unencumbered by colonial and neocolonial aesthetics.” Do you agree with that assessment?

NwT: The language question is central in all this. The younger generation are still continuing with the colonized mentality of the writers of my generation. The younger writers must be at the forefront in the reclamation of our languages.

RF: What role, if any, do you see the Internet playing in the struggle to decolonize language? Does it offer a new space for African languages to thrive—or does it, in practice, reinforce English as the default medium of global exchange?

NwT: African languages have to keep up with technology, The Internet is a new space in the struggle for decolonization.

RF: In your new book, you write, “If you know all the languages of the world except your mother tongue, you are enslaved. On the other hand, if you know your own language and add all the other languages of the world to it, you are empowered. Our choice is between intellectual enslavement and intellectual empowerment, and of course, I hope we choose the path of empowerment.” Reading that sentence today, in light of President Trump’s recent executive order designating English as the official language of the United States, it’s hard not to feel like we’re headed down a “path of enslavement.” The order rescinds federal language access protections and promotes English as a symbol of national cohesion—echoing the same logic of linguistic dominance you’ve long critiqued. I’d be curious to hear your thoughts on this.

NwT: That is a very retrogressive policy. I would have liked to hear him say that all Americans must know at least one of the Native American languages, in addition to English. One language is a very retrogressive policy that goes all the way back to the Old European attempts at definition of what constitutes one nation. America lives within a multilingual reality.

RF: You’ve famously called language “a war zone.” How do you maintain revolutionary optimism when this war seems so long and the victories so incremental?

NwT: Without contraries there is no progression, or so said William Blake. But the Hegelian idea is the same. Thesis > Anti-thesis > Synthesis.

RF: Your son Mũkoma wa Ngũgĩ’s poem “Hunting Words with My Father” ends with the line: “to hunt a word is to hunt a life.” When you read that line—“to hunt a word is to hunt a life”—what does it conjure for you today?

NwT: I wish, like I wish all writers in Africa, to hunt with African language—with African words.