As Trump Goes After Protected Status, Venezuelan Students Are “Terrified”

While those with TPS are safe on paper, the administration’s attempted revocation and ongoing legal battle has left many young immigrants—regardless of status—fearing detainment.

Venezuelan community leaders speak to the media as they protest against the suspension of Temporary Protected Status in Doral, Florida, on February 3, 2025.

(Chandan Khanna / Getty)Garcia pulled his Temporary Protected Status document and held it under a desk lamp at the Boston Public Library. As a Venezuelan migrant, this piece of paper was supposed to mean that he was protected against deportation in the United States for 18 more months. But in early February, Garcia—and the other 350,000 Venezuelan migrants in the United States—learned that their Temporary Protected Status (TPS) would expire on April 7.

The sudden revocation and ongoing legal battles left Venezuelan migrants scrambling to secure alternative legal means to remain in the country, all while trying to maintain their routines of work and school. And as deportations dominate the news, the fear of being deported—regardless of TPS status—is rapidly rising.

On March 31, US District Court Judge Edward Chen issued a court order temporarily blocking the termination of TPS—a designation for people who cannot return safely to their home country—just days before the protections were set to expire, buying Venezuelan TPS holders more time to proceed with legal efforts to remain in the US.

The initial revocation, led by DHS Secretary Kristi Noem, came just one month after Joe Biden extended TPS through October 2026 for Venezuelans—the largest group of TPS holders. Secretary Noem has said that allowing Venezuelan nationals to remain in the United States is contrary to the national interest, citing threats of Venezuelan gang activity. Yet about 90 percent of the migrants—the majority Venezuelan—deported to El Salvador prisons in the last month had no US criminal record.

Garcia doesn’t seem like much of a threat. He is unhoused. His bed: a space on the floor at the Boston Night Center. During the icy Boston winter, his days are spent searching for work and heat. Although he has applied for asylum, and his pending appointment with the immigration courts carries protection from deportation, Garcia still worries, even with the legal protection.

“I have my paperwork, my work permit, my ID,” he said, displaying an array of cards and documents on the library table. But he fears that his paperwork may not be enough to prevent DHS officers from pulling him off the street. Each morning, as Garcia’s face meets the icy chill of the alley in front of the shelter, the scariest part of his day begins. Leaving the shelter, his feet move fast—but not too fast. Raising his eyes momentarily, the tall, lanky man catches the glance of a woman on the street. Their three-second gaze feels like forever. In his head, thoughts run wild. “We can’t live like this.… I’m afraid to go out on the street,” he said, his voice low. “I swear, it scares me.”

With changes like TPS revocations happening so quickly, everything feels arbitrary, and immigrants—documented and undocumented—don’t know what to expect, says Victoria Miranda, a senior attorney with Lawyers for Civil Rights in Boston. “It’s kind of done in a way to create that chaos,” she said.

While fear and uncertainty pass through the Venezuelan communities, lawyers continue to fight back. These actions from the Trump administration didn’t come as a surprise to LCR, said Miranda. “They were anticipating this.”

The National TPS Alliance and Venezuelan recipients filed a lawsuit arguing that Noem and the DHS have no legal authority to undo the extension. In response, DHS released a statement on February 20, stating a return in integrity to an “abused and exploited” system. “President Trump and Secretary Noem are returning TPS to its original status: temporary.”

This is not the first time the Trump administration has set fire to TPS. “I don’t think it was much of a surprise,” said Miranda. In 2017, President Trump tried to block TPS, which was challenged in court and ultimately rescinded by former President Biden. Now, eight years later, TPS termination is heading back to the courts.

There were three separate legal TPS cases filed, one by LCR in Massachusetts, one in California, and another in Maryland, explained Miranda. “The California case got their date first.” When the Massachusetts and Maryland cases came up for hearing, their judges essentially deferred to the California ruling, recognizing its comprehensive nature and nationwide scope, she said.

The goal of these legal actions, according to Miranda, is to maintain the original TPS extension from the Biden administration and challenge what they view as illegal actions with racist roots. While the litigation timeline is uncertain—the process could potentially take years—the immediate result is that Venezuelan TPS holders will not be deportable as of the originally planned date, and LCR remains prepared to continue fighting the case if the government decides to appeal the California ruling.

The quick and diligent response she said, shows that legal organizations are buckling up, not giving out. “[The energy] is excited to fight the good fight, but also upset that we even have to do it in the first place.”

On paper, college students with TPS are safe, but silence has become another tactic for survival. “I think they are very aware,” said University of Massachusetts–Boston associate professor Luis Jimenez. “[Students] know that they’re vulnerable.” At least 900 students at over 128 colleges and universities across the country received notice that their visa status had been terminated or revoked. Although the affected students represent a small percentage of the more than 1.1 million international students in the United States, many of whom are finding their legal status reinstated from a new administration decision on April 25, the administration warns of more removals soon. Regardless of the back and forth, those on visas see themselves reflected in the cases, stirring up fear of who could be next.

At UMass Boston, one of the most diverse four-year colleges in the country, Jimenez is accustomed to staying after class to speak with students about their immigration status. Yet, this spring semester, something has shifted. Students have more and more questions, he said, yet fewer and fewer are asking about their own status concerns. They’re no longer asking, “What’s going to happen to me?” It’s more vague, he said, “like, ‘Well, I have a friend.’”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →Even without the pause, Venezuelan university students’ admissions status would not be threatened and information regarding their immigration status is still protected under federal law. But these federal protections are feeling less and less certain as fears of detainment or deportation ripple through classrooms.

Although universities, both private and public, cannot share information about a student’s immigration status without a court order, campuses are no longer a protected zone. On January 20, the Trump administration rescinded the 2021 policy that prohibited Immigration and Customs Enforcement from taking enforcement actions in protected areas, which includes college campuses. This means that if student TPS holders lose their status, they will be subject to deportation with the same legal designation on the streets as well as college campuses. “And [ICE has] every right to do it,” said Jimenez. On March 25, ICE detained a Tufts student in Somerville, Massachusetts, despite their having a valid F-1 visa.

Students and university groups have created informal “neighborhood watches” for sighting ICE officials throughout Boston campuses. Earlier this month, when a plainclothes DHS officer was spotted on Boston University campus, organizations immediately took to social media to warn the community. Although they are active in sharing news and information among themselves about student rights, many Latinx Student Groups and Student Immigrant Alliance Groups at Boston University, UMass Boston, and Harvard declined interviews or did not respond to The Nation for comment, and students within the clubs are hesitant to speak out individually. “They were honestly not keen to do this,” Jimenez said in an e-mail after speaking with his students. “They’re terrified of visibility.”

Garcia sighs and places his phone face down on the library table, then rests his head in his hands. As the weather turns warmer, he still finds himself hiding here among the books, scrolling through job applications and news feeds, his emotions ping-ponging between anxiety and ease.

The e-mail from the National TPS Alliance informing him of the pause renewed some hope that organizations like LCR are continuing to fight. But each morning, when another video of ICE detaining someone new despite their having legal status, surfaces, he prays that he won’t be next.

“One day I think my future is going well,” he said. “And the next, I feel like we want everything to matter, without anything actually mattering.”

More from The Nation

Springsteen Gets America in Ways Trump Never Will Springsteen Gets America in Ways Trump Never Will

And that reality has caused the president of the United States to lose it.

How Should Los Angeles Rebuild After the Fires? How Should Los Angeles Rebuild After the Fires?

In the aftermath of this year's catastrophic fires, architects and urban planners begin to consider how to rebuild.

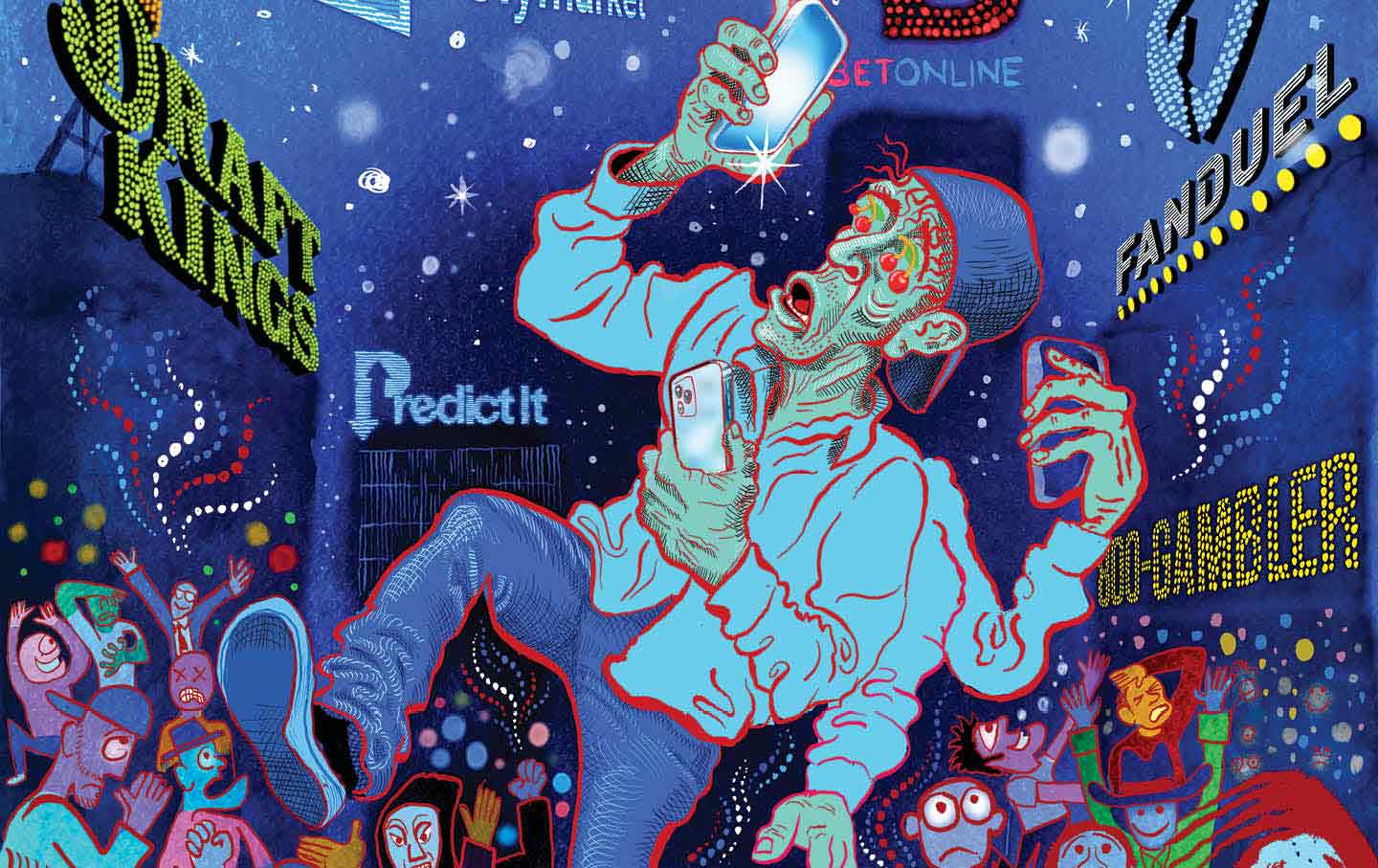

Welcome to Casino Capitalism 2.0 Welcome to Casino Capitalism 2.0

The legalization and rapid spread of sports betting has made problem gambling everyone’s problem.

An Open Letter to Clarence Thomas An Open Letter to Clarence Thomas

As the Trump administration tries to remake society along apartheid lines, your vote to stop the assault, however unlikely, is absolutely essential.

They All Signed the “Harper’s” Letter. Where Are They Now? They All Signed the “Harper’s” Letter. Where Are They Now?

Many of those who were loudest in denouncing cancel culture then are now curiously silent in the face of Donald Trump’s assaults on free speech.

How the Rich and Powerful Destroyed Free Speech How the Rich and Powerful Destroyed Free Speech

And how we get it back.