Do Not Forget That India and Pakistan Could Still End Up in a Nuclear War

Even after a ceasefire, the standoff over Kashmir risks escalating into something far worse if nationalist ideology wins out over realism.

For four days last week, war waged between India and Pakistan. Not a declared war, not a direct clash of ground troops, and not, thankfully, a general war—which, given the two countries’ nuclear arsenals, would necessarily be of unlimited potential. Instead, they fought with air strikes and air defenses, long-range artillery, and, in a contemporary twist, swarms of drones. As with past conflicts between India and Pakistan, the fighting was concentrated in the divided border region of Kashmir, which both countries claim in its entirety. As of Saturday the 10th, the two sides have settled into an uneasy ceasefire, but both militaries are still deployed for combat and practically all diplomatic cooperation has been cut off.

It wasn’t always thus. A quarter century ago, on a balmy day in February of 1999, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then India’s prime minister, traveled in person to Lahore, Pakistan, to sign a historic treaty aimed at reducing the risk of war between the two countries. He also held a press conference, where one journalist, a Pakistani woman, popped an unexpected question: Would the prime minister marry her? (Vajpayee was a lifelong bachelor with a colorful personal life.) The journalist added, wryly, that she would ask for only one thing as a wedding gift: sovereignty over Kashmir.

Neither footage nor transcript exists of the exchange, and it has since been clouded in apocrypha, most recently though its dramatization in a Bollywood puff-picture, I Am Atal. (The story does appear in contemporary parliamentary records.) Whatever the truth of the incident, Vajpayee, a famed orator and a poet in his spare time, is said to have answered without hesitation that he was indeed ready for the marriage, so long as the journalist could supply all of Pakistan as her dowry.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee was the first Indian prime minister from the right-wing, Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). He was also, in his way, a peacemaker. His visit to Lahore was the first by an Indian leader, and Pakistani politicians across the ideological spectrum paid him tribute after his death in 2018. By the standards of today’s BJP, now under the thumb of Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Vajpayee was a moderate. He famously eulogized his longtime political adversary Jawaharlal Nehru by declaring, “Mother India has lost her favorite prince.”

But Vajpayee was still a nationalist, his views forged by a career as an apparatchik in the same Hindu nationalist paramilitary that would produce Modi. His defining legacy is not his attempts at diplomacy but his fateful decision—explicable only by ideology, rather than any strategic logic—to publicly resume India’s nuclear weapons program, which had been effectively frozen since the 1970s. In May 1998, amid much religiously charged fanfare, India exploded five test bombs in the Rajasthan desert. In the most predictable of outcomes, Pakistan quickly responded with six tests of its own.

In a one bold step, India had thrown away its conventional military advantage over its rival—along with considerable international goodwill—and inaugurated a nuclear standoff against a country with a history of military coups, and which was then in the middle of a historically disastrous flirtation with Islamic fundamentalism. Taiwan, Ukraine, and the Middle East may receive more attention as potential nuclear flash points, but to date, India and Pakistan are the only two nuclear powers to have waged conventional warfare against each other.

On April 22, 2025, five gunmen opened fire on civilians in Pahalgam, Kashmir, killing 26: the trigger for the recent conflict. (India alleges that the attackers were Pakistan-backed Islamic terrorists; Pakistan has denied being involved. An Islamist group called the Resistance Front initially claimed credit for the attack, but it has since retracted.) When the Indian Ministry of Defense announced last Wednesday that it had begun carrying out air strikes across Pakistan in response to those deaths, it did so under the banner “Operation Sindoor.” “Sindoor” refers to a ubiquitous red cosmetic powder associated with marriage in Hinduism. In a traditional Hindu wedding, the groom applies the powder to the bride’s hairline; widows are meant to ceremonially wipe off their sindoor along with breaking their bangles, another symbol of matrimony.

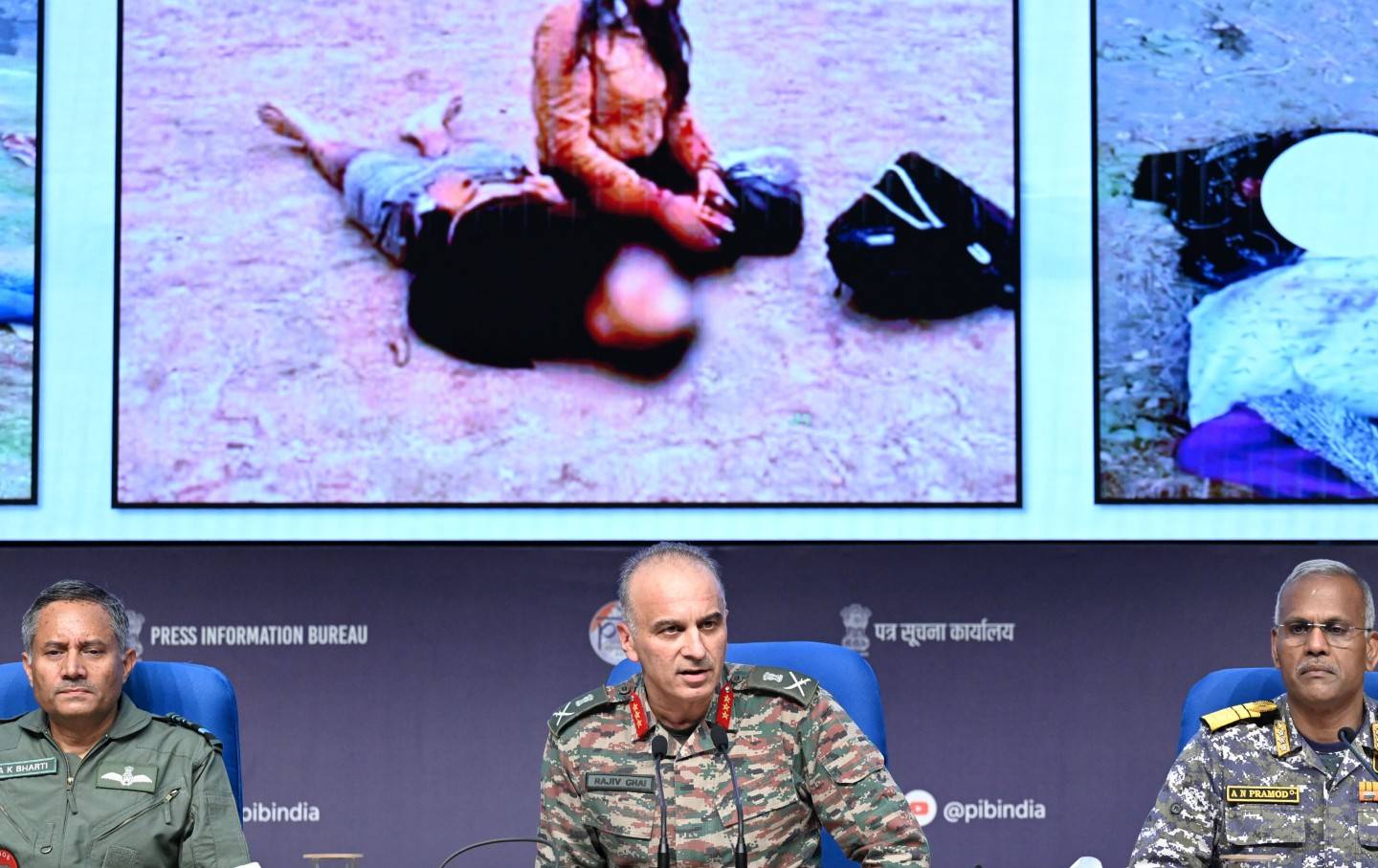

The Indian announcement was accompanied by a graphic, since widely shared on social media, of a tin of sindoor with the powder violently spilled across the page to unmistakably evoke a gunshot wound. The operation’s name is apparently inspired by a photograph of a woman, Himanshi Narwal, whose husband was shot dead in the attack in Pahalgam. Narwal and her husband, an officer in the Indian navy, were newlyweds visiting Kashmir on their honeymoon. The viral image shows Narwal slumped to her knees next to her husband’s lifeless corpse, her red marital bangles visible on her limp wrists.

For reasons that are yet unclear, all 26 of the dead at Pahalgam were men. The list of widows is long. Most of the victims were tourists, hailing from 14 different states across India. The attackers appear to have forced at least some of their victims to expose their genitals to verify their religion before killing them. The marriage metaphor, which in Vajpayee’s usage stood for friendly competition and hopes for reconciliation, has now become a war cry signifying the debasement of India’s marital virtue and the violent emasculation of its husbands.

The unstable emotional valence of that metaphor has been on display in the public saga of Himanshi Narwal. In the days after the attack, the image of her grief came to symbolize first the nation’s collective grief, then its growing rage. Her unlimited pain was meant to license unlimited retribution. Then, in her first public statement since losing her husband, she declared, “We don’t want people going against Muslims or Kashmiris. We want peace and only peace.” (She would later give another statement, in which she approved of Operation Sindoor and endorsed its name.) Instantly, Hindu nationalist Internet trolls, who had already exploded in a wave of Islamophobia after Pahalgam, unleashed hatred on Narwal. Much of their vitriol took on the form of sexist slut-shaming—this against someone who until that moment had been cast as a patriotic idol of feminine dignity. She was meant to play the passive victim, a damsel in destress—a familiar trope of Hindu nationalist mythologizing. When she stepped out of that role, the self-appointed gatekeepers of that mythos torched her at its altar.

When the British departed India in the summer of 1947, Kashmir was an independent monarchy with a largely Muslim population. Many of its residents hoped that it could remain that way, perhaps with a democratic form of government in place of a princely one. Instead, over the next frenzied months, the pristine land in the foothills of the Himalaya was divided up between the new countries of India and Pakistan—partly by law, mostly by force. The 1947–48 Indo-Pakistani War was the first of three the countries would fight over the status of Kashmir, with the most recent in 1999. In 2019, they came close to a fourth, after a suicide bomber from a Pakistan-linked terror group killed 40 police officers near Srinagar, the capital of Indian Kashmir. The jingoistic fanfare around the attack and subsequent retaliatory air campaign is widely credited with helping Modi to a landslide win in that year’s national elections.

Pakistan’s claim to Kashmir has always been based on demographic continuity and on the fact that, at the time of partition, three-quarters of the territory’s population was Muslim. That claim, however, depends on a deeper, unspoken, one: the so-called “Two-Nation Theory,” the political credo of Mohammed Ali Jinnah, Pakistan’s first governor-general. Jinnah believed Muslims in the subcontinent were a separate nation who needed and deserved a separate state. Pakistan was founded on that theory; India has always rejected it. The fact of Muslim preponderance is an argument in Pakistan’s favor only if one already accepts Jinnah’s view that Islam pertains exclusively to Pakistan, and not also to India, where 200 million Muslims live.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →India’s claim has a legal basis in the fact that, in 1947, the departing Maharaja of princely Kashmir—faced with a rebellion and marauding Pakistani militias—signed a document handing his kingdom over to India. But Jawarharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, also wanted Kashmir to validate his country’s foundation as a secular state and to undermine Pakistan’s status as a confessional one. He benefited in that quest from the fact that Kashmir’s leading political movement at the time, the National Conference, was a secular and socialist one, on the model of Nehru’s own Indian National Congress.

In the decades after, however, India largely squandered its high ground by refusing to hold a referendum on Kashmir’s final status while violently suppressing any hint of separatist activity. Pakistan, for its part, has been a poisonous neighbor, sponsoring an insurgency beginning in the 1990s that has killed 40,000 people. With the ascent of Hindu nationalism under Modi, India’s rhetoric has begun to focus more on the plight of Kashmir’s Hindu minority, while also incorporating messianic arguments about civilizational purity and the ultimate dissolution of Pakistan.

When the Indian portion of Kashmir formally became a state of that country, it did so under a special constitutional provision, Article 370, that gave it autonomy over internal matters. This was Nehru’s concession to the Kashmiri sovereigntist ambitions that evaporated in India and Pakistan’s warring. The Hindu right opposed the gambit from its inception. For them, Article 370 was triply offensive: a compromise with Islam, a threat to the “integrity and indivisibility” of India, and mockery of the principle of equality between states. In August of 2019, heady with the buzz of reelection, Narendra Modi’s BJP government passed a bill to revoke Article 370. Kashmir had enjoyed all the privileges of statehood and then some (a fact other states could reasonably object to); with the stroke of a pen, it was downgraded to a “union territory,” meaning that the central government in New Delhi now rules it directly.

Government officials and BJP ideologues promised that the end of Kashmir’s constitutional carve-out would mean the “full integration” of the territory into India, which would, in turn, yield peace and economic progress. Stripped of its special status, Kashmir would simply revert to normalcy. At the time the change took effect, however, “normalcy” turned out to entail police curfews, an Internet blackout, and the jailing of thousands of alleged dissidents without trial. Evidently, the government sensed that not everyone would see political integration as the boon that New Delhi insisted it was.

More strikingly, Indian Kashmir remains the most militarized place in the world. Five hundred thousand troops are deployed there over an area slightly larger than Maryland, as many as the United States sent to Vietnam at the peak of that war. Until now, the government could at least claim to be producing results: New development projects are in the works for Kashmir, and tourism has soared without producing a noticeable uptick in violence. That illusion shattered with the attack at Pahalgam; other, grander illusions may suffer the same fate in the coming weeks.

In his foreign policy, Narendra Modi has long tried to strike a balance between assertiveness and affability: between the confidence befitting a nuclear-armed economic powerhouse and the fraternalism of what India’s leaders often call its role as Vishvaguru—“teacher to the world.” Like most Indian prime ministers before him, Modi is eager to be seen as a great-power leader. But even he understands that India’s best asset is its soft power, which includes a rich tradition of nonalignment and a self-consciously spiritual approach to global affairs. The other, related tension in India’s foreign policy is between realism and idealism. Modi and his surrogates constantly invoke a single instance, in October 2022, where Modi publicly told Vladimir Putin that “now is not a time for war.” This pastoral gesture is presumably meant to have made up for the hundreds of millions of barrels of crude oil that India, acting out of pure self-interest, has bought from Russia since it invaded Ukraine.

In global terms, realism may be winning out in the balance of India’s foreign-policy thinking. But Kashmir has a special hold on the Indian political psyche, as it does for Pakistan. To nationalists on both sides of the border, Kashmir is like Taiwan is to China: Without total dominion over this one peripheral piece of territory, the identity of the whole nation is compromised. Ideology, not sober strategic calculus, governs how the two countries act in Kashmir, just as it governs their choice to build nuclear weapons and point them at each other.

The ceasefire that went into effect on Saturday was reportedly violated almost instantly but now seems to be holding. Yet the conflict is only frozen, not resolved. For the moment, its victims are the same ones that have suffered for the last 70 years: the people of Kashmir and their legitimate democratic aspirations, now plus the 26 dead at Pahalgam and an unclear number on both sides in the fighting last week. India and Pakistan each hold the power to instantly add millions more to the list of victims if they fail to follow the path of de-escalation.

More from The Nation

The Nakba Has Never Ended The Nakba Has Never Ended

In Gaza, the boundary marking past and present has become indistinct. Nineteen forty-eight is not over—it is unfolding again, and in more violent and destructive ways.

Jean-Luc Mélenchon Explains How His Party Took Down the Right-Wing Jean-Luc Mélenchon Explains How His Party Took Down the Right-Wing

La France Insoumise built its electoral power and took down a rising far-right.

The New Pope Delivers a Consistent Message on Gaza: Ceasefire! The New Pope Delivers a Consistent Message on Gaza: Ceasefire!

Pope Leo XIV has echoed his predecessor’s urgent call for an end to the assault that has killed more than 52,000 Palestinians.

The Return of the Nuclear Threat The Return of the Nuclear Threat

While most of the world looked away, a new nuclear arms race has broken out between the US, Russia, and China, raising the risk of nuclear confrontation to the highest in decades....

India’s Attack on Pakistan Was a Strategic Flop India’s Attack on Pakistan Was a Strategic Flop

It was a conflict with no winners. But in the end, India lost.

What It Feels Like to Starve What It Feels Like to Starve

What we are witnessing now in Gaza is not a famine of nature. It is famine as a weapon of mass destruction.